Are we on the brink of saving rainforests?

Until now saving rainforests seemed like an impossible mission. But the world is now warming to the idea that a proposed solution to help address climate change could offer a new way to unlock the value of forest without cutting it down.

Rhett A. Butler | mongabay.com | July 22, 2009

Deep in the Brazilian Amazon, members of the Surui tribe are developing a scheme that will reward them for protecting their rainforest home from encroachment by ranchers and illegal loggers.

The project, initiated by the Surui themselves, will bring jobs as park guards and deliver health clinics, computers, and schools that will help youths retain traditional knowledge and cultural ties to the forest. Surprisingly, the states of California, Wisconsin and Illinois may finance the endeavor as part of their climate change mitigation programs.

Deforestation in southern Laos (January 2009). Photos by Rhett A. Butler

As unlikely as it may sound, this collaboration could become a reality under a far-reaching initiative to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD), a climate change mitigation mechanism currently under consideration by U.S. legislators and in international discussions for a "framework" on climate change. Supporters say REDD could send billions of dollars a year to developing nations for conserving their rainforests, while preserving biodiversity; protecting ecosystem services like rainfall regulation, watershed functions, and erosion control; promoting rural development in some of the world's poorest, and in some cases, least, governed regions; and breaking a deadlock that has stalled international climate negotiations for over a decade, since the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.

The premise of REDD is straightforward: tropical forests store roughly 25 percent of the planet's terrestrial carbon, more than 300 billion tons. When forests are cut—their vegetation burned and timber converted into wood products—much of this carbon is released in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. The clearing of 50,000 square miles of tropical forest annually accounts for roughly 20 percent of global emissions from human activities—a share larger than all the world's planes, ships, cars, and trucks combined. In other words, despite the attention given to the fuel efficiency of cars and the number of flights taken by celebrities, parking all the world's jets and cars still wouldn't offset the annual emissions from global deforestation.

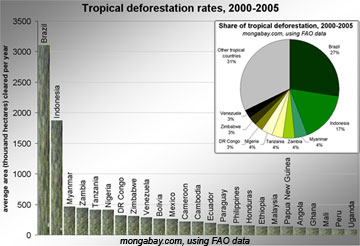

Tropical deforestation rates from 2000-2005, ranked in descending order by the highest amount of average annual forest loss for 25 countries based on data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Click to enlarge

But reducing deforestation is no simple effort. Forests are being destroyed as a consequence of global economic forces—demand for timber, pulpwood, beef, soybeans, and palm oil—as well as subsistence farming. Slowing or eliminating deforestation means addressing these underlying drivers by making forests valuable as living entities, rather than solely for what can be produced when they're cut. And the issue goes beyond economics. Good governance, including law enforcement, recognition of land rights, and fair distribution of benefits, is the issue that will make or break REDD.

Thinking REDD

The idea of forestalling climate change by saving forests is not new, but it has had to win its way slowly. The Kyoto Protocol went a different direction, and critics of REDD fear it would be too complex to manage in a world economic scheme for climate rescue. (Some critics also think most plans don't do enough to address overconsumption by developed nations.)

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan (May 2009). Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

REDD suffers, like all such schemes, from the difficulty of explaining itself in terms non-specialists can understand. Carbons markets, offsets, cap-and-trade—all these have been in the language for years now, but the topics still seem esoteric to many. This "my-eyes-glaze-over" syndrome may be especially acute in the United States, whose government declined to join the Kyoto Protocol. But still, there are the Surui people—and if an Amazonian tribe can get help in saving its home forests by partnering with U.S. states, maybe the rest of us can get some handle on the idea.

What's more, the whole subject of climate change and its mitigation has gotten a renewed boost with the Obama administration's support of cap-and-trade—the concept of legally limiting a region's greenhouse-gas emissions and encouraging trade in the "credits" earned by industries that meet or exceed the standards. (A debate continues, however, over cap-and-trade vis-a-vis what are sometimes seen simply as "pay-to-pollute" offsets.)

The Birth—and death—of forest carbon

Protecting forests as a climate mitigation strategy has a history in the United States. American power companies—including American Electric Power (AEP), PacificCorp, BP Amoco, and others—spent millions of dollars in the 1990s to protect at-risk forests in Belize, Bolivia, and Brazil in hopes of getting early-action credit for "offsetting" their greenhouse gas emissions by preventing deforestation.

Rainforest in Borneo (April 2008). Photos by Rhett A. Butler

The Noel Kempff Mercado Climate Action Project, as the Bolivian initiative was known, would become model for "avoided deforestation." Project designers carefully calculated a baseline deforestation rate using business-as-usual scenarios; set up monitoring and verification systems; accounted for leakage—deforestation that would be displaced to other areas by the protected status of the park; and set up a system of incentives for people in and around the protected area.

Tia Nelson, daughter of the late Gaylord Nelson, the governor and senator who founded Earth Day, is now co-chairwoman of the Governor's Task Force on Global Warming and executive secretary of the Wisconsin Board of Commissioners of Public Lands. She was a key participant in the development of early forest-protection mechanisms as a deputy director of the Climate Change Program at the Nature Conservancy (TNC), a conservation group based in Washington D.C., which provided technical and scientific support for the projects.

"I was fascinated by the idea that companies would pay to conserve forests as a climate change mitigation strategy," she said. "Noel Kempff was particularly well-designed."

But the utility of Noel Kempff and other forest conservation projects was limited by the exclusion of forest conservation from the climate agreement reached in Kyoto in 1997. For many environmental groups, forest carbon was at best a distraction from the key issues of Kyoto, and at worst an insidious way for polluting industries to continue emitting greenhouse gases by paying poor countries to reduce their own emissions. When the United States pushed for inclusion in the Protocol of carbon sinks like forests, opponents saw it as an attempt by the world's largest polluter to avoid emissions cuts.

Stuart Eizenstat, a prominent attorney at Covington & Burling, former U.S. ambassador to the European Union, and the lead U.S. negotiator during the Kyoto talks, said that while justifications for conserving forests seemed strong, bigger concerns loomed over Kyoto, including emissions trading and contributions of developing countries to mitigation.

Deforestation-induced erosion in Madagascar (October 2004)

"We pushed for sinks because we were looking for every conceivable way to both engage developing countries and reduce costs. We knew that cost was going to be the most critical issue as it is today," Eizenstat said.

In the end, the rancor over offsets led to the exclusion of forest conservation from Kyoto. Forests were included in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)—Kyoto's attempt to involve developing countries in a climate solution. CDM allowed for afforestation (planting of new lands) and reforestation projects, but not for "avoided deforestation," although the provision was short-lived. Afforestation and reforestation was relegated to temporary credits in the Marrakesh Accords in 2001 and completely excluded from the Emissions Trading System (ETS), the European Union's compliance market for carbon. All this greatly limited the value of forestry credits.

Nelson said the decision not to include forest conservation in Kyoto came as a disappointment, but not a surprise. A lot of environmentalists argued that offsets were not a solution to reducing industrial emissions, a sentiment that remains strong today.

"It was a pretty lonely battle at the time," Nelson said. "I was hopeful that we had a good case but there were only a few voices arguing for avoided deforestation then."

The decision to exclude forests from Kyoto was a controversial one, producing shouting matches and bitter rifts between environmental groups. It would also prove costly to tropical forests and their inhabitants.

Oil palm plantations and logged over forest in Malaysian Borneo (April 2008). While much of the forest land converted for oil palm plantations in Malaysia has been logged or otherwise been zoned for logging, expansion at the expense of natural and protected forest does occur in the country. Reserve borders are sometimes redrawn to facilitate logging and conversion to plantations. Photo by Rhett Butler.

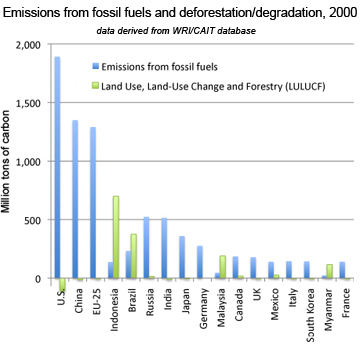

The years following Kyoto saw a surge in deforestation, particularly in two countries with the most extensive forest cover: Brazil and Indonesia. In Brazil, deforestation increased nearly year by year between 1997 and 2004, peaking at 10,600 square miles in 2004, an area the size of Massachusetts. The story in Indonesia was even worse. The collapse of the Suharto regime in 1997 ushered in a period of chaos, resulting in unprecedented destruction of forests. Loggers and oil palm plantation developers cleared and burned vast areas, facilitated by one of the strongest el Niño events on record. When the smoke cleared, more than 25,000 square miles had burned in Indonesian Borneo alone, unleashing upward of 2 billion tons of carbon. All told, since Kyoto's exclusion, the two countries have lost more than 160,000 square miles of forest, an area nearly the size of California, releasing billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere and placing the two countries among the top emitters in the world—a position far outpacing their industrial output.

But deforestation wasn't limited to Brazil and Indonesia. With no incentives to keep forests standing, deforestation accelerated around the planet, especially in primary forests, the richest biologically and most carbon-dense form of forest and the most irreplaceable. Centuries-old rainforests were cleared for cattle pasture, oil palm plantations, mechanized soy farms, and industrial pulpwood. Environmentalists continued to sound the alarm, perhaps failing to realize their own role in the rising carnage. Meanwhile, supporters of avoided deforestation regrouped, expanded their reach, and explored new ways to include forests in a global climate deal. To be workable, a proposal would need to overcome serious technical, political, and ideological obstacles.

Rebirth of the forest initiative

A breakthrough came from an unlikely source: an academic paper. A team of American and Brazilian researchers analyzed the issues that kept forests out of the Kyoto Protocol and came up with a solution that addressed the most pressing concern, "leakage"—the idea that project-based schemes like CDM couldn't guarantee that shutting down deforestation in one area wouldn't simply shift it to another. The authors, including Márcio Santilli, Paulo Moutinho, Stephan Schwartzman, Daniel Nepstad, and Carlos Nobre, proposed a system of national accounting, meaning that countries would have to commit to national-level, rather than project-level, reductions in deforestation. The concept suggested a mechanism that would look a lot like trading between two capped systems, rather than just offsetting emissions.

Pastureland and transition forest in Mato Grosso, Brazil (April 2009). Since 2003 Brazil has set aside 523,592 square kilometers of protected areas, accounting for 74 percent of the total land area protected worldwide during that period. Photo by Rhett Butler.

"The publication of ‘Tropical deforestation and the Kyoto Protocol" was a very important development because it created a scientific space—and a policy space—where you could actually talk about reducing emissions from deforestation and put the leakage question to one side. It didn't completely resolve the leakage question but it greatly tempered it." Annie Petsonk, a policy expert at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), said.

A crucial parallel development was the emergence of a negotiating block—later to become known as the Coalition for Rainforest Nations—that would enable developing countries to participate meaningfully in reducing emissions and would help quiet complaints that Kyoto didn't do enough to include all countries.

In 2005 Papua New Guinea joined forces with other forest countries to form the Coalition of Rainforest Nations with Kevin Conrad as executive director. A key member of the coalition was Costa Rica, a country lauded by the international community for transforming itself from a high deforester to a model of conservation.

"One of my first official delegations was to Costa Rica to find out how they turned their deforestation rate around," Conrad said. "They said, 'Yes, we did it, but we've been taxing ourselves. No one's been helping us with it.' Well, we knew Costa Rica might be able to do that but for most of us, there was no way. We would need a source of funding."

The Coalition went to the U.N. Conference of the Parties (COP) meeting in Montreal in 2005 and immediately met opposition from the United States, which was content doing nothing on climate. The U.S. delegation told Conrad it would kill the Coalition's proposal, fearing that if developing countries put forth a plan committing to robust and meaningful reductions in greenhouse gases, the United States would no longer have an excuse not to take action on climate.

"The U.S. was going to block us simply for that," Conrad said.

Conrad engineered a strategy for delaying U.S. action during the Montreal talks, persuading dozens of countries supportive of the proposal to push their voting buttons ahead of the United States.

"If the U.S. went first, all the naysayers would pile on," he said. "But if they were fortieth following a long trail of positives I was hoping they wouldn't be able to kill the proposal."

Sure enough the United States agreed to give the proposal two years, sending it out to committee with the expectation that it would collapse under the technical challenges of measuring, verifying, and monitoring emissions from deforestation. Should the proposal make it to COP 13 in Bali in December 2007, the U.S. delegation promised to kill the measure then.

History took a different turn, though.

Lowland rainforest in Costa Rica (March 2009). Photo by Rhett Butler.

By 2007 advancements in science had shown that not only were verification and monitoring of forest carbon possible, but that emissions from deforestation and degradation were so significant that they couldn't be excluded and keep atmospheric carbon dioxide levels under 450 parts-per-million, a level seen by many scientists as a critical climate tipping point. The Rainforest Coalition had a strong case that actions on forests by tropical countries could make a substantial contribution to the battle against climate change. But the Coalition still had to go up against the United States In Bali, where the U.S. delegation was attempting to block progress towards a post-Kyoto agreement. Conrad issued a direct challenge:

"We ask for your leadership, but if for some reason you're not willing to lead, leave it to the rest of us. Please get out of the way."

Minutes later the U.S. delegation capitulated, paving the way for the Bali Action Plan, which recognized the critical role tropical forests play in regulating climate.

Bali proved to be a watershed moment for REDD. During the meeting, Norway unveiled its International Climate and Forests Initiative, a plan to commit some 3 billion krone ($500 million at the time) per year to rainforest conservation, a sum still unmatched by any other donor. The World Bank announced a $300-million fund, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), to jumpstart REDD projects in developing countries, and several other countries voiced support for the concept of REDD. Since Bali, momentum has only grown. In 2008, Britain and Norway put $200 million towards the Congo Basin Forest Fund to fund forest conservation activities in Central Africa; the U.N. has launched it own REDD fund; and Prince Charles made saving rainforests his signature cause, developing the Prince's Rainforest Project to bring business and political leaders around to supporting conservation. His efforts culminated in a historic meeting between heads of state to discuss rainforest conservation ahead of the G20 summit in April 2009.

Oil palm plantation and logged-over forest in Borneo (April 2008).

Mining road in Suriname (June 2008). Photos by Rhett Butler.

Developing countries have also become involved. Ecuador offered up a large tract of rainforest in the eastern Amazon as a giant forest carbon offset, while a group of 26 African countries in East, Central and Southern Africa announced the African Climate Solution, a plan to seek carbon financing for forest conservation, rural development, and poverty alleviation. Meanwhile, dozens of other countries have applied to the U.N. REDD program and the FCPF to begin receiving funds for REDD readiness activities. But the biggest news came from Brazil, which announced the formation of a $21 billion fund to reduce deforestation in the Amazon by 70 percent within 10 years, preventing an estimated 4.8 billion tons of carbon that would have been emitted under a business-as-usual scenario.

Owning to its lack of a climate policy, the United States has been slow to move on the concept of avoided deforestation, but a broad base of interests, including conservationists, development experts, scientists, and industry groups, has helped pushed it to the front of the climate agenda. Groups like Forest Carbon Dialog and Avoided Deforestation Partners, have played a critical role in working through difficult policy questions, fostering partnerships and strategic alliances between sometimes adversarial parties, helping draft legislative language, and informing policymakers of the multiple benefits of REDD.

"Having a dialog among companies, NGOs, and other stakeholders about how to get forest carbon on the table in a U.S. policy context have been very important," said Petsonk of EDF.

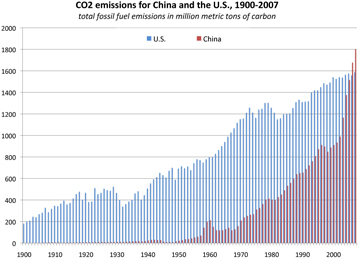

Emissions from fossil fuels for the U.S. and China, 1900-2007

The efforts have paid off, with REDD figuring into last year's failed Lieberman‐Warner Senate Bill and the American Climate and Energy Security Act (ACES) narrowly passed by the House of Representatives in June. The current version of ACES, which is now in the Senate, seeks to achieve supplemental emissions reductions of at least 720 million tons of carbon dioxide in 2020 and a cumulative amount of at least 6 billion tons carbon dioxide by the end of 2025 through avoided deforestation. The proposal is equivalent to the United States conserving 34,000 square miles of rainforests in developing countries and would boost U.S. emissions reductions targets from 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 to 27 percent if fully exploited.

U.S. climate legislation is particularly important for progress on REDD. Without it, the U.S. delegation to the December 2009 Conference of Parties (COP15) in Copenhagen will not be able to bring much to the negotiating table, Eizenstat said.

"It is impossible for the U.S. delegation to go beyond the emissions targets that Congress will set in legislation," he said. "The administration cannot go further than Congress will allow. Congressional legislation will thus be a very important step."

National GHG emissions from industrial sources (electricity generation, transportation, buildings, etc) and LULUCF, 2000. Note that some countries have negative emissions from LULUCF meaning they these sources are a net carbon sink. Also note that the E.U. is listed in addition to its individual member countries.

Supporters say that beyond the environmental benefits of REDD, there are good reasons for the U.S. Congress to include REDD provisions in climate legislation, including reducing compliance costs for American business under a cap-and-trade system, engaging developing countries in a climate framework, and bolstering security in potentially worrisome areas through sustainable development and climate change mitigation.

"Climate change impacts could include crop failures and drought, creating instability and the potential mass movement of ‘eco-migrants,'" Eizenstat said. "But strong forest provisions would offer multiple co-benefits."

Tracy Johns, a forest policy expert who is co-leader of the Woods Hole Research Center's REDD Initiative, agrees.

"From a domestic standpoint one of the things that makes REDD a really attractive policy option is that it is a mechanism to encourage developing countries to take on emissions reductions goals," she explained. "At the same time it offers to these developing countries a potential pathway to use forests in a sustainable matter for development. Finally REDD offers a very interesting and potentially very effective cost containment measure U.S. businesses under cap-and-trade program. REDD will make it easier for the U.S. to reduce emissions further at a lower cost."

Clearcutting in the Peruvian Amazon (October 2005). Photo by Rhett Butler.

While still evolving, the U.S. position appears to be leaning towards a financing mechanism for REDD that includes both fund-based and market-based financing mechanism for REDD, a position shared by the Coalition for Rainforest Nations and by Australia. Financing remains one of the most contentious issues for REDD, with Brazil calling for an aid-based fund and Europe hesitant to allow forest carbon into its compliance market for fear it could cause the price of carbon to fall. Market advocates say that fund-based approaches will be subject to political whims and won't generate the kind of money needed to reduce deforestation at the scale and pace necessary to meet emission reduction targets.

But the critical issue in the market debate really is the fungibility of credits—whether countries can count carbon credits against their emissions. ("Fungibility" means that economic assets are exchangeable in the satisfaction of obligations.) Some Europeans countries are worried that the REDD credits will undermine low-carbon technologies without meaningfully reducing emissions, while Brazil doesn't like the idea of letting industrialized countries off the hook for their emissions. Environmental groups are split. Some call any sort off offsetting a "false solution" to climate changes; others say strong caps will greatly reduce the risk of the market for carbon credits being flooded.

"The central issue that is a critical impediment to progress on REDD and really to anything dealing with global warming is that the United States is not in the international game," Stephan Schwartzman, co-author of the seminal paper on compensated reduction of emissions from deforestation, said. "The U.S. has not actually begun to reduce its emissions nor created a cap-and-trade system. As long as that's the case, European policymakers are justifiably concerned about guarding the integrity of their carbon market."

Small-holder deforestation in Suriname (June 2008). Photo by Rhett Butler.

"In the international discussion, among some NGOs there's still a sense that we can somehow avoid the risks of the market funding all of this with one version or another of public funding. But government priorities change and public funds are limited," Schwartzman said.

"A robust market mechanism is going to be critical to having this work. If there are too many good, real reductions from avoided deforestation out there, then tighten the cap. How hard is that?"

William Boyd, a professor at the University of Colorado Law School who has worked closely on REDD policy issues, agrees that a capped system can help avoid market flooding. A Greenpeace study, released at Bonn, has warned that in an unlimited market, carbon prices could drop by up to 75 percent.

"This isn't an extension of pure project-based offsets," Boyd said "The system is moving towards a national accounting framework where a country only get credits if it reduces emissions below a baseline that could progressively ratchet down over time—it might go to zero deforestation at some point. At that point you're trading between two capped sectors or two capped systems. Very different than the idea of offsets."

Healthy forest and recently cleared forest adjacent to Tanjung Puting National Park in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) (February 2006). Photos by Rhett Butler

Regardless of the eventual source of funding, there is no question that considerable funds need to be generated to effectively reduce deforestation. A recent report from the Meridian Institute on behalf of the Norwegian government estimates that to achieve a 50 percent reduction in deforestation by 2020, REDD will need a commitment of 2 billion per year in 2010, increasing to 10 billion per year in 2014 for capacity building, readiness activities, and demonstration projects. The report suggests financing could come through a global fund, financed through donations generated by auctioning of emission allowances, fuel surcharges, or development aid. Prince Charles has suggested a different approach: a rainforest bond issue to provide emergency funding.

Beyond the money

Beyond the issue of financing, there are other points of contention, including how to establish baselines, especially in countries and regions that have managed to maintain forest cover or have already reduced deforestation rates dramatically. Some countries—like Costa Rica—want credit for early action, while others are pushing for elevated baselines to account for potential deforestation, positions that raise eyebrows among those concerned about the integrity of REDD. But as Kevin Conrad of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations puts it, "If we don't provide incentives for countries that have so far maintained their forests, but otherwise have land suitable for conversion, then those forests are going to fall."

Negotiators must further work out whether to include emissions from degradation of other carbon-dense ecosystems like peatlands, which in some years may contribute more than 2 billion tons in emissions. Wetlands International is adamant that peatlands be part of a climate pact—especially in light of Indonesia's recent announcement that it will open millions of hectares of swampy wetlands to oil palm cultivation. The move—ostensibly to expand production of palm oil, which can be used as a feedstock for biofuels—could trigger millions of tons of emissions and destroy habitat critical for endangered species, including the orangutan and Sumatran tiger.

Another issue—known as permanence—stems from the integrity of forest carbon stocks and the capacity of a forest to retain carbon in the future. Critics ask how it can be assured that a forest protected for REDD won't be logged, accidentally burned, or damaged by a storm, flood, or drought, reducing its capacity to store carbon. The issue is a significant one given the forecast impacts of climate change in places like the Southern Amazon. The 2005 drought—caused by abnormally high temperatures in the Atlantic, rather than el Niño—killed millions of trees and turned large expanses of the Amazon into a tinderbox. Thousands of square miles of forest went up in smoke, releasing more than 100 million metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere.

Eroded hillsides in Madagascar (October 2004). Photo by Rhett Butler

REDD advocates say this issue can be addressed partly through safeguard required under criteria like the Voluntary Carbon Standard (VCS) and the Climate, Community, and Biodiversity Standards (CCB) as well as emerging insurance products and national reserve accounts proposed by the Coalition for Rainforest Nations. But the best protection may be the forests themselves. Studies suggest that reducing deforestation can be one of the most important factors in increasing forests' resistance to the effects of climate change.

New technology, including a new class of remote sensing applications, will help scientists and forest managers monitor forests for degradation. Satellites and high-altitude aircraft equipped with lasers and high-resolution sensors can map the structure of the forest, greatly increasing the accuracy of carbon estimates as well as documenting changes in carbon stock. CLASLite, an advanced processing application for monitoring tropical deforestation, and Google Earth are greatly expanding the availability of forest cover data to scientists, policymakers, and the general public.

An issue of payment

But great satellite imagery won't resolve a thorny issue arising from the need to directly address drivers of deforestation. Given that industrial activities today account for the bulk of deforestation, a successful REDD mechanism may mean paying agents of deforestation—forestry firms and agribusiness—to cease their activities. The concept doesn't sit well many environmentalists, but in cases where landowners are within the law, REDD becomes a way to encourage loggers, oil palm plantation developers, large-scale farmers, and ranchers to leave their forests standing.

"Without economic incentives, standing forest will always lose out to pressures from the market," explained John Carter, an American rancher in the Brazilian Amazon, who heads Alianca da Terra, an NGO that works to encourage environmental stewardship among beef producers in the Amazon. "Land appreciation and production value are at the end of the day what determine land use. In order for REDD to work, all landowners—whether they be Indians, ranchers, or farmers—should be allowed to participate."

Carter believes that forest reserves—required under Brazilian law for landowners in the Amazon—should be eligible for payments under REDD.

Some environmentalists worry that REDD could become a tool for "greenwashing," whereby firms mask their environmental damage by buying REDD credits. This concern touches on the entire debate about "offsets," a concept that activist groups like the World Rainforest Movement and the Rainforest Foundation UK find deeply troubling. Buying REDD credits, however, will not offer environmental transgressors sanctuary from environmental campaigns and freely accessible satellite imagery. Green groups are already putting Google Earth to use for monitoring deforestation and other activities.

Forestry remains a controversial issue in REDD discussions. Some environmental activists complain that REDD may allow selective logging in old-growth forests, the most biodiverse and carbon-dense ecosystems. Others argue conversely that sustainable logging should be allowed as a source of income for forest holders, including indigenous communities. Recent reports of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlight the value of reduced-impact logging as a mitigation strategy. But the impact of logging depends largely on forestry rules and governance structures, an area of particular concern to the Ecosystems Climate Alliance (ECA), a coalition of eight environmental and rights groups.

Issues of consumerism, governance

The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a member of the ECA that works on international trade and demand issues, believes REDD should incorporate rules for demand in consuming countries, since deforestation is as much driven by market demand in industrialized nations as it is by poverty in developing nations.

"My major concern is that until we talk about these demand issues in a meaningful way, we aren't talking about a real solution," EIA Forest Campaigns Director Andrea Johnson said.

Johnson believes funds for supplemental activities under the Waxman-Markey bill could be directed towards joint implementation of demand-side laws like the U.S. Lacey Act, which is used to fight illegal logging by requiring companies to respect environmental laws in the countries from which they obtain plant and wildlife products.

Jihan Gearon of the Indigenous Environmental Network, an indigenous rights coalition, said, "Offset mechanisms, including REDD, do not address the real problem causing climate change. The major driver of climate change is the historical and current burning of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—to feed the unsustainable consumption needs of industrialized countries, like the United States. We have to prioritize and focus on changing these unsustainable consumption patterns, which are responsible for not only climate change but also a host of other issues including pollution to land, water, air, animals, and people."

Governance also is a critical issue for the success of REDD—it ranks among the top priorities among REDD designers, but good governance is difficult in frontier areas where most deforestation is occurring. Development agencies are positioning REDD as a vehicle to deliver services and protections that vast amounts of aid have so far failed to provide—a tall order for a conservation initiative. Still, REDD has at least two advantages over prior mechanisms: it offers a wide range of benefits and will be performance-based. If a country fails to reduce deforestation by meaningfully addressing drivers of deforestation, it won't collect.

But this new governance regime raises other questions, especially in areas where rights are poorly defined. This is particularly important for forest-dwelling communities and indigenous people, who despite having occupied lands for years or generations may still lack formal title, or even basic rights, to land and resources. Many groups fear that regulation could cause them to be further disadvantaged, depriving them of their land as well as leaving them out of carbon payments. Some paint a nightmare scenario of forced displacement at the hands of carbon speculators.

"REDD projects do not help indigenous peoples and forest peoples," Gearon said. "In fact they hurt these communities and take away access and rights to forests, traditional territories, and medicines. Our principal hope and concern for the REDD mechanism, as well as other market-based solutions to climate change, is they be rejected because they are false solutions to climate change."

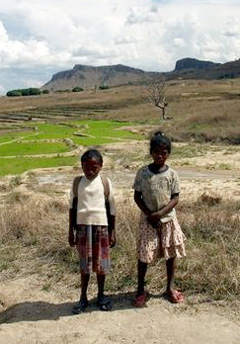

School children in Madagascar (October 2004). Half of Madagascar's children under five years of age are malnourished. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

The Indigenous Environmental Network and other groups have called for the inclusion of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a treaty signed by the majority of the world's countries in 2007, in REDD. But REDD designers say the stipulation is unlikely because negotiators from countries that haven't signed the Declaration (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States) can't sign an agreement that binds them to a treaty their countries have not ratified. Many native leaders are lobbying for a mandate that all REDD programs seek the "free, prior, and informed consent" of local people.

But in spite of these concerns, the consensus among coalitions representing forest people is that forest conservation should be included in a climate framework. Some groups are even supportive of a market mechanism, recognizing that a well-designed mechanism is better than the status quo.

The Surui are an example. The tribe actively sought out its own carbon project, first focusing on reforestation of areas that had been illegally logged, but then exploring REDD as a means to generate income to defend its forest home. Almir Surui, a Surui chief who has become the public face of the tribe, said forest conservation is also a way to maintain culture in a place where there are strong bonds between land and society.

But in pioneering their REDD project, the Surui have run up against some obstacles, indicating that the forest carbon initiative hasn't been designed with indigenous issues in mind. For example, by virtue of being good stewards of their forests the Surui encounter the same problem faced by countries with high forest cover and low deforestation rates: the REDD process doesn't reward them for their success in maintaining their forest cover even as forests around their reservation fell to bulldozers and loggers.

"REDD should enhance recognition that indigenous people have maintained the state of their forests, not penalize them for this stewardship," said Vasco van Roosmalen, director of the Amazon Conservation Team-Brazil, an NGO that has helped the Surui develop an indigenous park-guards program and biocultural maps of their territories. "The Surui are guardians of forest carbon."

And while the debate continues, participants aren't sitting on the sidelines – REDD projects are sprouting around the world. Although these projects are limited to voluntary markets (like the Chicago Climate Exchange) where carbon fetches a fraction of the price seen in compliance markets (E.U. ETS), the number is nonetheless increasing due to the appetite of corporations to appear environmentally responsible. After all protecting habitat for endangered species and providing health and education to forest-dwelling communities is perhaps more compelling to consumers than projects to capture emissions from agricultural waste.

"If you had a choice between carbon credits generated when a commercial factory pig farm reduces its toxic methane emissions, or carbon credits from a threatened natural forest that brings with them protection of elephants, lions, cheetah, giraffe and 54 other large mammal species which one would you prefer?" said Mike Korchinsky, Founder and President of Wildlife Works, a firm that just signed the first REDD deal in Kenya.

The Nhambita project in Mozambique has won acclaims for its levels of transparency and the benefits it is delivering to people in a desperately poor area. The project was initiated by Envirotrade, a London-based carbon finance outfit.

Philip Powell, founder of Envirotrade, explains: "The Nhambita project employs more than 150 people and compensates thousands of farmers who voluntarily sign agreements to confront destructive forest fires, conserve forest and replant trees on their lands. Our greatest long-term challenge is to deliver equitable and significant benefits directly to individuals and communities that are the forest custodians. We believe the best way to advance this is through transparent reporting and a commitment to fair compensation for measured changes in forest and land management."

Meanwhile, the Juma project in the Amazonas state of Brazil, which is the first project in the world to attain the Climate, Community and Biodiversity Alliance's Gold Standard for its safeguards, is compensating 6,000 families who voluntarily agree to limit forest cutting. The project is expected to reduce emissions in an at-risk forest area by 190 million tons of carbon dioxide by 2050.

John O. Niles, a REDD expert with the Tropical Forest Group, a forest policy think tank, said that REDD offers the potential to make the world a lot more aware of indigenous issues.

"REDD will put a microscope on these issues and will be infinitely better than the status quo," he said. "For decades, capitalists, socialists, private companies, governments and local operators have blasted into tropical communities, razed forests and moved on with little concern for the fact that they just denuded the land. I think a UN-driven system of incentives for keeping forests, a system of oversight with some transparency, and the strong voice of critical observers will lead to more positive outcomes more of the time. Anything via the UNFCCC is likely to be an improvement over plantation forestry, industrial logging, large infrastructure projects or commercial agriculture."

Dan Nepstad, an ecologist formerly of the Woods Hole Research Institute but now with the Moore Foundation, agrees.

"We have heads of state listening to indigenous leaders – that is unheard of."

Moving forward

Given myriad issues, will REDD designers be able to develop a workable framework? People involved in REDD discussions think so.

"I think the chances are very strong that if we get a climate agreement in Copenhagen that REDD will be a part of it," said Tracy Johns of the Woods Hole Research Center. "All of the stakeholders that have been involved in the REDD process in recent years—governments, NGOs, the private sector, indigenous peoples—have done a lot of work and made a lot of progress on the issues and challenges for REDD. I think in many ways the REDD negotiation process is more advanced than many of the other lines of negotiation that are under way for Copenhagen."

While the details for REDD are far from settled and obstacles remain, there is growing support for the phased approach proposed by the Coalition for Rainforest Nations and presented in the Meridian report for the Norwegian government. In the first phase, countries would receive funds—as they would through the World Bank's FCPF, the UN REDD Program, or another voluntary mechanism—to develop a national REDD strategy including consultation with indigenous peoples and local communities, capacity building, and pilot projects.

Phase 2 would support reform of land tenure and forestry laws, sustainable forest management initiatives, and payments for environmental services to local communities, indigenous peoples, and other parties. Funding would be performance-based and come from a global fund financed by voluntary donations, auctioning of emissions allowances, and possibly fuel and carbon taxes in some countries.

Rainforest pool in Belize (May 2008). Photo by Rhett Butler.

Phase 3 would include compliance-grade monitoring, reporting, and verification of emissions against agreed reference levels. It would likely be financed by the sale of REDD units within global compliance markets or a non-market compliance mechanism. Supporters of the phased approach say it accommodates both fund- and market-based mechanisms, includes provisions for indigenous people, offers flexibility allowing countries at different levels of capacity to participate, and considers many of the outstanding concerns for REDD.

For conservationists REDD offers the best hope that rainforests—including their biodiversity, ecosystem services, and resident peoples—can be saved.

"REDD is being asked to do a lot of things—improving governance, promoting sustainable development, and mitigating climate change, but the potential benefits are so great, it's a chance worth taking," said Schwartzman, whose paper helped get things started.

"As long as forests are worth more dead than alive, it's going to be extremely difficult, and probably ultimately impossible, to preserve more than fragments of the world's forests. Creating that positive economic value for living forests is a key part of the solution to the global warming crisis."

Box 1: The Coalition for Rainforest Nations

The Coalition for Rainforest Nations was born out of a conflict between the World Bank and Papua New Guinea (PNG), a country better known for its cultural diversity (more than 800 languages are spoken across its rugged mountainous terrain) than its political acumen. But the dispute over a $50 million payment could someday lead to billions of dollars in payments for protecting global rainforests. PNG could be one of the largest beneficiaries.

In 2001 the World Bank came to PNG with a loan proposal: around $50 million over 10 years for the country to cease all logging and transition to sustainable forest management. But PNG turned it down, arguing that the offer was too low to meet the needs of the forest communities that had signed the logging contracts. The loan rejection triggered a standoff between PNG and the bank, leading to damaging accusations and an ugly fight.

"These communities want to save the forests, which are the basis for society and culture in New Guinea," said Kevin Conrad, an American born to parents living in Papua New Guinea and now a lead climate negotiator for the G-77 and China. "But at the same time these communities need schools, health and access to markets to develop."

Conrad went to graduate school at Columbia University with the intention is exploring ways for PNG to capitalize on its forests without destroying them. In New York he met with the World Bank and was surprised to find that it was the world's largest carbon trader. He asked the bank how one of its departments could be demanding that New Guinea stop logging, while another was trading carbon.

"I asked the World Bank, 'Why not put your efforts together and give us something we can work with?'"

The World Bank told Conrad the idea was a non-starter because the Kyoto Protocol didn't allow forest conservation projects.

"So I asked, 'what if we change the Kyoto Protocol?'

The World Bank told him that if he changed the Kyoto Protocol then all options would be open.

"So that was the basis of our submission in 2005."

Box 2: National vs. Sub-National

There is heated debate over the scale and scope of REDD projects. Because few countries are expected to have national REDD programs up-and-running anytime soon, developers are first starting with individual projects within countries—a sub-national approach—that are ready for market-based compensation now. But eventually these projects will need to be integrated into a national system to avoid leakage and other issues. The process of integration remains contentious and some fear that early stage projects will never be recognized in national level accounting, depriving them of access to lucrative compliance markets.